Places Of The Heart

-

Places Of The Heart

-

Angel Island

April 25th, 1993

One more of mushrooms, this late winter

turns against all odds into an early spring.Intense, wet, yellow parasols thrust towards

the sun, beige buttons nestling in lichen—The moss— orange, gold platters full of rain

fall over onto beds of bay laurel leaves. PaleFibers floating in water— soft infant’s touch—

wet kiss on tiny earlobes, glistening fineStrands of hair— new as life’s fresh scent. Before

Coast Miwok, in boats woven of tule reed, usingDeep strokes paddling through straits, set dense

woods on fire to clear land to hunt. Now in the ferry,Using binoculars, guidebooks. White oaks encircle

the summit trail— filtering light—our heads bent,Footsteps resolute, even-steady— brush strokes on

our daughter’s corn silk hair— her ringlets escapingIntention of a ponytail, coiling around her neck.

Cucumber vines wind up manzanita—On the path, a clump of Narcissus— white as milk,

fragrant as a breast. Hairpin turn—Hummingbird hovers in a canyon of madrone. Pale green

wings flutter in the light— relentless work to stay put.She— soul of my mother. Dive! Dive down to earth

for nectar! In one straight line, she has gone—I am left. I’ve been waiting my whole life like this.

Loss— strongest emotion— a knife in the chestBefore the Coast Miwok expelled from this island across

the bay to Mission Dolores.This morning, access for hikers is argued in Sacramento.

A blue butterfly shudders across the path.At the very top of the trail, we call out names: Mt. Tam,

Diablo, Hamilton, San Bruno, Umunhum, Ring Mountain.The line of vision— a bright umbilicus. Before this, navel

of the bay— used to quarantine diseased soldiersReturning from the Philippines, to detain undesirable

immigrants from the far east. Today we are held in joy—Island from still deep waters— bawling. Banished angels

with palms outstretched, reaching for the light. -

The Color Walk

November 6, 1992

Peninsula SchoolIt is more prevalent than I had thought.

I am thinking of my color and writing

with kids at a giant oval table.Sarah’s hair tie—iridescent,

my slim-hipped daughter’s jeans,

Allie’s dangling earrings— chairs aroundA table pick me up— carry me outside

to our walk again—on a magic comforter—

the tarp draped over several boxes inA pick-up truck— delicate blossoms

on a neighbor’s bush, a scrub jay on

the Douglas fir scolding a squirrel—A van slowed down for our procession

— silence of twenty twelve-year-olds,

hands clutched behind their backsEyes focused intently at the tousled head

of a kindergartener nestled in branches of

an apple tree, eyes dreamy, torso relaxed.Under the blue t-shirt— the voice of a mother

calling out to a roving teacher, ‘Is he OK?”

Other children gathering at a painted slide—Staring at us pilgrims, strange future glimpses

of themselves, deliberateness of steps. We made

a turn into the school yard— icing and candles onA cupcake, in the sign for no school on Armistice

day, license plates for the whole state of California,

love in the eyes of Aleta—The edges of the large pieces of poster board,

she carries to the classroom, the crumpled

candy wrapper on the ground left over fromHalloween— deepest of colors among red

and yellow, the sign over the math lab

says “eggplant” painted psychedelicAs we write inside, even now, our pens,

pencils spiraling from the clearest sky. -

Hans and Katrina

I.

Hearts’ breath cast in porcelain,

Hans and Katrina stopped in

the middle of their country dance.They closed their eyes for 59 years

on hand-stained coffee tables, oak

hi-fi cabinets, walnut dressers intoTheir space — my parents’ shared life.

Hans’ glossy white head tilted under

a jaunty peasant’s cap, white jacket,Baggy striped blue pants, and wooden

shoes, the color of hay, his large hands

hidden, empty under his elbows. He laidDown his tools before dancing with Katrina,

the edges of white bonnet pointed blue

flowers skyward. Smooth camel-coloredHair hiding her delicate ears. Her lively

eyes turned downward towards the dark

tulips on her skirt. Her one possession,An opening for flowers in Katrina’s

starched apron — all hollow

inside her narrow waist.II.

In my early years, Hans and Katrina stood still

on the second level of my parents’ two-tiered

end table. Pulling myself up from the shaggyGrey rug to see them. I learned not to touch,

stroke, lick their shiny cold surfaces. Later,

growing, understanding things MotherTreasured. The first year of World War II,

She snapped up Hans and Katrina;

two figurines kept losing their heads.My mom sighed, then repaired with

yellow glue. My fingers tracing tracks.

They moved every time we did.Cherishing their decorative, cheerful,

silent veneer, their polished exterior,

noticing their mouths—merely dots.Years later, Mom and I counted the

homes we’d lived in with Hans and

Katrina. Sixteen!III.

In her cactus garden, Mom walked me

down a meandering path she laid from

shards of terra cotta, broken pots.Remembering the nightshirts Mom

made from my father’s dress shirts,

I could see bordered in pink, blue,

zigzag trim along the neckline,

under arms, around shirttails.I recalled dresses sewed from wide swirling

skirts cast-off from my aunts’ Sunday frocks.

Mom broke silence in the garden, asking whatI wanted to keep once she was gone.

What lasts? My lips twitched,

Hans and Katrina.IV.

I wanted to hurl those figurines across time —

and America all the way to Guthrie, Oklahoma,

shattering the two against the bronze markerStill alive near the grave of Adelia Hofstader. I

never did though. I thought of great-grandmother,

Crazy Addie, they called her, a real woman,Coming as a girl from Holland to Galveston, Texas.

At 15, she spent the night clinging to a palm tree

during the hurricane, lived when her family died,Made crazy quilts, was taken aboard an orphan

ship to Mexico, taught children to read, married

a Scotsman, bore son Robert, daughter Dencie,My Grandma who grew up on the farm in Kansas,

studied math, married a preacher, moved every

Two years, lost her first baby to unsterile scalpels

in a hospital in Boston.She bore the next four children on the kitchen table.

Ruth was her daughter, my mother, the third child,

renowned for broad shoulders.Dencie called Ruth “my little peacemaker.”

Ruth did what was expected, made the best grades,

promised a college education out east, ran againstThe Great Depression, graduated valedictorian at

Oklahoma University, her father being president,Worked at bookstores, floral shops, engaged on the

eve of Pearl Harbor, married January 30th, 1942 inSeven yards of white taffeta, sewn by her sister,

Mary Lee, following my father, an air force cadet,

up, down the west coast, working in peach canneries,

scarred her ladylike hands. Ruth who bore me,Patria: the name means fatherland. The name came

from a woman my mom met in the great war, a woman

with a beautiful smile— my namesake— Patria Thorn.V.

A terrible stillness has overcome me. As if your beloved

things, mom, grandma, great-grandma, are lost.I am stranded here far away from your rushes and rivers.

I escaped your prairie land, to find California with its techWizards and wildfires, with its redwoods and calm blue ocean.

I rejected all but a few of the world of your thingsBehind. And I am lonely. Our offsprings are beginning to

desire to hold the beloved things of the ancestors.Hear me grandmothers. I am the blossom in your apron,

the dance at the edge of your love.We are learning to care for things that last over time.

-

Desert Hawks at Easter

“We are put on earth a little space that

we may learn to bear the beams of love.”

William BlakeTogether, two circle, then soar— far above the

dusty heat of prickly desert floor—

feathered gliders, spin—

turn the invisible strings of their desire.Black lace wings fall— surge

to weave through blue updrafts of appetite.

From redwood porch, they

suspend our Easter meal of ham and veal.The children wriggle out— leap their bare feet—

pound the deck— providing hot breathy music

for hawks aspiring the courtship dance.We two arise— lift our wings to shield aching eyes.

Sharp with ambition, aiming to follow high spirals,

we’re carved by hooked beaks of allure.Talons interlocked— grandparents sit alone, wishing to

chase that narrow shaft at rest, their bird souls coming—

then go free, at willWith neither song nor aim— in peace, they glide

in and out of the light. -

From Our Rented Cottage

From our rented cottage, we heard

the plaintive crowing of the roosters

s the birds chirp tentatively.The frogs croon all night in the creek—

plotting out their amorous desires,

jewels, their intentions of melding.We are the chorus in the tree branches.

What does our music foretell?

We know things you humans do not dare tell.You have said we do not know of the future.

This is not evident to us. There is insistence

in our bird song.The whir of the cars intertwines in the breeze

gentle and insistent as the pink money plant

right outside our door. A chicken withexquisite brown feathers pecks along

the garden path. How do these beings

relate and declare interdependence?Spotted goats and black furry young

bide behind the fence with brown ducks.

They scurry upon the arrival of barking blackand white dogs. The bird song is clear

though sparse. The sound of the creek

moving over the boulders is constant.The flight of the sparrow from tree to

wooden fence top is an inquiry into threat.

They all wonder if they will live long now.We want to talk to them, to apologize, to ask

if they will require anything from our species

— probably not. We have been architectsof their doom. They sing. We were told long

go it was our destiny to sing. We now know

our destiny is to listen, to ask, to intone —to admit how our interrelationship with

the land where the birds exist and

to imagine how we might aid themThis needs to be our focus rather than the fear

of illness and dying of our kind. We need to

honor that we are all interrelated. That thisIs the path to the wild and possible future.

-

Remembering Morning Before the Storm

Mt. Tamalpais

February 9, 1992Weeds in the garden fingers pulling up the roots snags

combing out secrets tangled in blue grape hyacinthHelen called last night— list to bring for ceremony:

cold weather clothing, rattle, plastic to sit on, a lunch.In St. Patrick’s fields, leaning back against a fallen branch

grey skeletal eucalyptus curves strong smell of mintStruggling to Leah’s car, early morning, stuffing fleece jacket,

pants, yellow boots under arm, juggling tea — bag lunch.Wet ground full around my legs hips everywhere

startled yellow mustard sprouting eyesLeah laughed at me. The peninsula — balmy even at seven,

morning before the storm ended the drought.

Her down vest sufficient. I, overprepared, as usual.

regret avoidance of a lone homeless man.Perched deep overhead, a great horned owl hoots,

ignorance of earth’s messages.Leah’s pretty face strained, worried over her interaction with

Josie— leader in the ceremony, we will attend on Mt. Tamalpais.

She told me her concerns— confidentiality and photography.Wind rattling grasses sheltering toadstools, just burst ladybugs

retrieving time only to give it back light—earlier now and longer.We gathered that morning before the storm at Marguerite’s—

so long since I’d seen her — once after storytelling evening

last fall. She hadn’t seen me for forever, seemed glad.The rolling nature of memories— these forty acres on

loan to me the lemon pepper grove, the olives, and scrub oaks.

When they build houses over them, it will be time to leave.

Where is my home?I drive up to Mt. Tam with Helen, Joan, Vivian—

older friends make comments showing lack of understanding.

Talk droned on— past disappointments—lost dreams.

Helen seemed off base.Down the path around the seminary — four nuns striding,

hands behind their backs headpieces flapping like the wings

of white pelicans— married to God— legitimate and free.Envy? No, Helen— not off base. What I need is time.

We turned on the car radio— no word of the storm.

Supporting projects of others at expense of my own—

she tells me I have a history of this.Dust in brown hills reservoir near empty— crystals springs

still gray clouds across the sky wheels speeding past

the daytime crescent moon.Joan and Vivian promote financial planning,—

women need to be independent—

children come back after college.

Do I need this?Each bend in the road, sky swept, water streaked,

indigo patches of winter sun. Many twists behind,

thin red leaves— eucalyptus.Parking car in designated place, wind is bitter, cold. Helen gives

out gloves, hats, scarves, feeds us carrots, tuna sandwiches.Walking straight up Mt. Tam— the trail steep towards

serpentine outcroppings. Stopping several times always

in shelter of the trees— what am I to them?A slight, noisy thing. Helen reminds if I wonder— can they hear?

Yet, they are my teachers— knowledge waiting to be passed on.

Wanting to be a student of the great temperate forest beginning

in California— stretching along the coast to the southern tip of

Alaska, I hear her laugh at my notions.A cypress bough— thirsty, encumbered by a golden eagle—

expanse of green— trees take up more space than buildings.

I give myself up to the trees— I can trust them.Fearing poems taken from me without ceremony, a dear friend

offered to reproduce them on fine linen, mail them in red, blue

cardboard. Her attentions easing this acute sensation of tearing.The gnarled arms of oak mother sheltering fifteen worshippers

sitting tailor style, smudging with sage passing, the backbone

of an egret. Making a plan to circle the bay once a month

in a year of Sundays.When my daughter had her first period, Leah wrapped

red velvet ribbon around her, then me, then cut the tie with

kitchen shears. Afterwards, a bath, advice for my daughter,

meditation, solace for me in the evening of Alicia’s meadow.Upwards the father— one massive redwood shaft — three

branches at the very top—the trunk a rusty—

transformation of the Gila— storage for acorn

hundreds of holes dozens of rows—a third of seeds still in

storage — carnage of the rest strewn about the base.Lying under this eucalyptus, I recall Ohlone practice of the

menstrual hut, giving back to the earth. My youngest daughter

has had her twelfth birthday. I have cut my hair.

What belongs under the ground?The frailty of the strands— disintegration of fibers — fear to

write my best to have it judged. Fear to find out what best is.

Inevitability in the retreat of the sun delicious this afternoon,

pleasure eating its pale peeled fruit.Without words, we form a line to creep over the stony face of

Mt. Tam, Josie laid out a spiral— little pieces of granite.

The resonance of the earth is particularly strong. She says lie

down at one place, sit at the second location. We do this one by one.The legend of the Miwok princess sleeping inside this mountain—

at least five hundred years—a refusal to awaken until people

come in peace. My turn— spread out on the granite.

A virgin washed over with red — hurt — pivot of survival.When young, mother said the most important relationship—

the only relationship— between man and wife, is the physical.Hands, palm down, on my knees at the second stone seat,

it is orange — the color of thoughts racing through the spiral.

Our centered hands hold the sky explosion of golden balls.Helen asks me to come with her to grassy precipice a hundred

yards away. She says she came to this spot 18 years ago when

she was 45 to find out if this were her home.Kneeling on grass beside her, keeping time, seeing her wrinkles

softening, hearing the prayer to the land— her connections

huge kite strings spanning the continent fierceness of

wind and clouds the colors deep in this waterI cannot stay on this precipice, needing shelter of trees.

Helen comes with me. Lying down, she covers me with a soft

fringed scarf— at 44, needing to know where my home is.The low oak rustling of dry leaves inside my eyes dampness,

and the glistening of tissue— reflection— pink light— roses—

stems and petals weaving for the longest time,

sensation of even the slightest change. -

Your Room

This must be where you live now, I mean really live—

your new house. It bathes us in yellow light—

the color saffron. It suffuses everything.Standing in a jasmine robe, you welcome me

to the base of your low oak platform—

steps like a stage. You motion me there,

gingerly openThe brass lock to a mahogany chest. Under low

piles of flax, you uncover two teak statues, unwrap,

hand them to me. I examine each one slowly, handle

with care— great wonder. Their flat features stylized,Extraordinary from Africa, Central America nowhere

perhaps—surely priceless— a scent of lemons in

their contours. These smooth ones may have been

your children— a long while past. Looking up,You placed your arm around the chestnut body of an old

man merged with a cello. Kindly, you uncoil your elbow,

wrist, allow me take the cello down to dance. Lightly, I tell

how I prefer instruments to menWho never do such things for me. The more I dance,

the more light flows into your room, even flatware is gold,

drapes warble like larks. -

Sappho Café

It rains most days outside the Sappho Café.

Inside the counterman serves petal pink ham,

sunny side up eggs, white toast triangles,

coffee, to soggy men in plaid flannel shirts.Pulling a green wool cap over his black curls,

running out front, a man fills a tank with gasoline.

That morning, requiring neither food nor gasoline,Walking inside, I saw, thumbtacked to the wall, an

emerald green shirt, ornamented with a Greek poet,

She wove her dance through the Delphic columns.I purchased three shirts and left. Many cars pass

through Sappho. Few stay at the café nor at the

turquoise trailer behind. No other structures standIn the town of Sappho, existing and celebrating a fork

on Route 101, diverges there with Route 112 traveling

northwest to Port Neah. There archaeologists andMakah Indians excavated, restored a fifteenth century

village, thus, uncovering a cedar bark technology,

blankets of bark interlaced with crimson woodpeckerFeathers, russet dog hairs, cedar utensils, richly

carved with men-in-shells, owls, whales, canoes.

On the established road, continuing in semi-circularFashion— southwest, then east to the Hoh Rain forest.

Ferns as tall as ten-year-olds grow. Their elders, Sitka spruce, shoot up skywards, yet their branches laden withVenerable moss, lean to whisper — even to drip — a lattice of advice. I have traveled both roads. Only once did I stop at the Sappho Café.

I cannot say when I’ll return.

-

Dragonfly in May

Land of Medicine Buddha

Santa Cruz, California

May 2, 1992Egg

This water is murky with what is alive.

Moss curls up from the soft bottom.

Tendrils creep around cement

edges of the heart-shaped pond.Twelve carp swim in indolent waves

ignorant of white bread floating

over their thick brown home.

A periwinkle flower falls, driftsUnder a plant with star-shaped leaves.

Its branch lurches under the weight

of a scarlet dragonfly with wings

of clear gauze. In the slight breeze,She shivers, takes off, hovers, flies,

lands briefly on the thin lip of a leaf,

returns to the star-shaped plant

overlooking the pond.She dashes about the water

looking for insects— drawing

circles and circles. For a second,

she kneels her spiny legsOn pearl blossoms of miners lettuce.

Rising to harass a small white moth,

she touches down on forget-me-nots

in the shade of the loquat.Finally, her bright body quivers

— darts for broad-scaled wings

of a Monarch butterfly.Winged Adult

I belong to a large family of toothed beings.

My ancestors had wing spans of two and a half feet.

I have shed my skin twelve timesWhen I climb out of the pond onto a rock or reed.

My wings cannot be folded—flying faster than any

swallow— folding my legs up like a basket to capture

my prey.In flight, I mate, then devour mosquitoes and butterflies.

I lay my eggs on the water. -

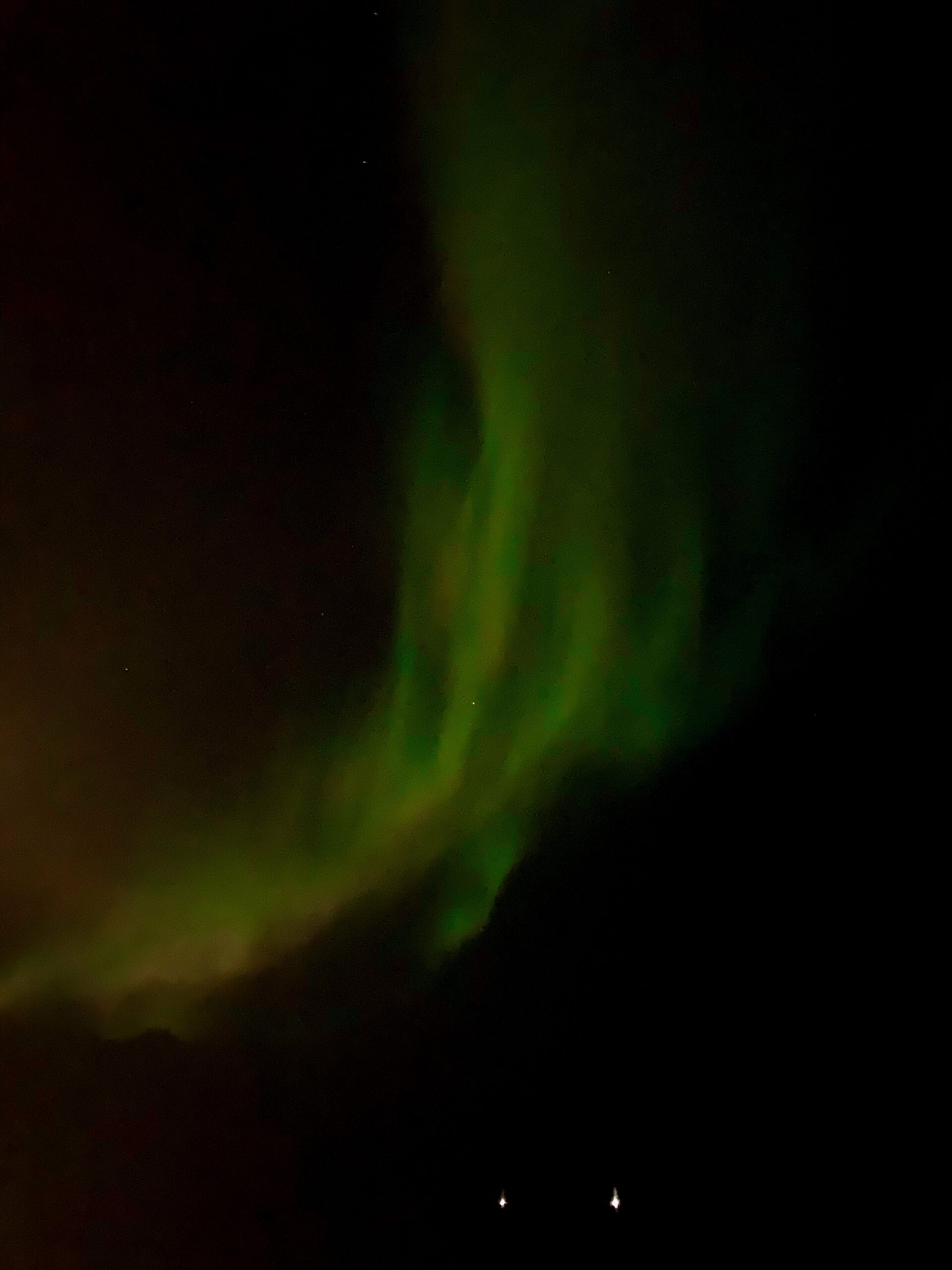

Aurora Borealis

We who would witness Aurora Borealis stand on the deck

of our ship and lift our eyes.Will it take three nights or three decades to form

the questions?What moves Spirit?

Are we specks of star dust, exploding as we reach

atmosphere’s unending birth?Will reindeer, cod, birch, and stone be dazzled?

Will we seize Aurora’s wonder?

Will we sigh and moan?

Will Aurora yield vast rays of purple, green, and white?

Will the vast rays dance, limber and spacious, cold and

windy amongst the stars?Will unnamed northern beings see them in the inner

reaches of their eyes?

-

First Night

We, held captive by a diagnosis of doom,

by a time table of loss, look up, desperate.In polar night, solar storms send particles

of amazement— bursting in the atmosphere.Spirit cascades with color take our thoughts away.

A sense of irrelevance— that great blessing,

overwhelms us, swirling with awe.We humans will rob Earth Mother of her children for

the next 100 million years— we wonder where and

who we are?Who shall be enchanted by Aurora’s glory

over epochs in the absence of life?

How cold will be our remembering?Surely not, we who come from this northern realm,

have sprung from Fjord of the Trolls.

Certainly not we—so full of questions.Ancestors from the belly of tall ships that left Norwegian

shores question Spirit—Will Aurora careen and unfold as

long as the Sun yields its unstoppable particles?Will Aurora’s streams of light hold latent souls

until Mother gives birth once again to the world?

Will Spirit ever answer them?Suddenly, a lump appears in the throat of Verdandi,

poet of the present, bound for the Arctic skies.

She is mourning the lives of her foremothers.

She has spent little or no time with them.Generations of sky-obsessed grandmothers sense

saliva pouring over as she swallows hard,

time and time again.Verdandi fights tears as hard and bitter sorrow stings.

Her sister Urd, poet of the past, tends Verdandi, who

utters cries of joy for time before the Black Death.Then elk, foxes, wolves, sperm whale, covered

each fjord bay, teeming with vigor. Tilting her

head back to face Aurora in despair—Inhaling fierce, icy breaths, Urd reminds Verdandi

of woeful loneliness of the Sami, their grandmothers’

people, shuttled—sea to mountains—Inland waterways—interior farms. Verdandi and Urd beg

Aurora to say if this migration were made for anything but

lucre? They wait for answers.Aurora throws down white curtains— Borealis sweeps

the deck with blistering cold air. Verdandi continues her

lament, as Urd begins grieving the lives of Sami childrenForced to attend Norwegian school, forbidden to speak

their Samski language— swallowing hard as ever,

Verdandi asks why such atrocities persistOther than inclining to destroy the culture of the

indigenous. After inhaling more polar air, Verdandi

breathes out mist— asks why endless confiscation

of their lands:Dislocation, German scorching, destruction of alpine

forests. No answer here. So knowing enquiry is endless

— still Urd and Verdandi persist the inquisition. Why did

one-godded Christians swallow their religion—Rob them of the worship of spirits in every fauna,

flora, landform, stone? Why did the government kill

73,000 reindeer, inedible after Chernobyl?

The ensuing silence hurts.The sisters stand still in the fury of the north, of Borealis.

Verdandi pulls the coat around her neck as Urd touches

her sister’s tears, frozen stiff just beneath her eyes.Together on this midnight ship — a community of shivers

floating over the Arctic Circle, swaying in the realm of

Borealis. Aurora invited Odin, god and ruler of Asgard,

revered by all Vikings, to join us tonight.Odin still resides in Valhalla, where he prepares for the

gods to be extinguished— the world to be rendered anew.

He needed Valkyries on horseback carrying spears,

shields to Valhalla.Aurora illuminates the sky with reflections of Valkyries’

armor. We strain our current vision to see where

reflections rise. Borealis howls, exposes the lump

Verdandi sought to hide.The ship passes Tromsø— Aurora hurtles white curtains

down like majestic ladders of pure white silk. The lump

advances and recedes in Verdandi’s throat. The days of

the dead and living scatterBehind Aurora’s celestial veil. Urd can see her sister’s

lump under delicate cover of her exposed neck skin.

Borealis unmasks all that again and again.

It is futile to hide.Night rolls by all the places, jewels on Aurora’s crown —

Trondheim, Bodø, Logenfren, form a ring around the

sphere of the Great Mother in a glowing circle. Once

we were a community of the Norwegian sea—Its waves black as octopus ink, icebergs evanescent as

our lives. Will stories, farms, mountains, alpine forests,

tundra of Norway melt back into the sea

like the Sami under duress?Skuld— poet of the future, ponders if Verdandi’s lump

will melt away too? And with that, dissolve Urd’s key

to the past? Will climate collapse define the future

height of the ocean?Will it rise to drown Oslo and Bergen in its wake?

Will Thor’s hammer descend and hit the birch trees

on the Arctic coastline beach— chasing, lounging

ghostly coral back to the ocean floor?Verdandi’s tears dissolve again like icebergs, leaving

salt water, forgetting the One who paints the sky with

star dust. Skuld sees the future twelve years away—

destiny sides with climate collapses for good.Will we forsake the One who dances with messengers of

the Sun? Will we be torn from Spirit utterly? Immense

twirling of Aurora’s green spiral illuminates the night sky

— a vast funnel, then fizzles.The salt crusting on Verdandi’s chipped and burning lips

is swallowed— joy erupts in the color purple connecting

with the stars. Memories of Odin and Freyja

making love under Orion’s belt—Connected only with a backward glance— consumed

in the melting. Our Viking blood spilled in the thawing

creek will mix with poems, peace nomination, runes,

dreams.As Aurora Borealis pretends to slumber, Verdandi

dreams of a Blessing Way, held in the nubile mountains

of Santa Cruz. Verdandi and Loki, the trickster,

live on the land.Vanessa asks Verdandi, “Will you invoke an ancestor

of the land to bless my brimming babe?” Honored,

Verdandi stands up, breathes deeply, energy surging

through her esophagus into the throat.She says “Mother Mountain Lion is ancestor of acres of

chaparral and oak. She is the One who watches over.

Blessed be.”Six nights later Vanessa gives birth. Loki and Verdandi

are ordered not to disturb. Three nights after the birth,

reading at home across the parking lot from Vanessa,

they hear a bone-chilling scream.Next thing Vanessa is on the phone announcing loudly

a mountain lion on their front deck. They hear Quentin’s

and Clive’s quick footprints. Loki grabs his flashlight,—

Verdandi joins him running.They are shown large foot prints. Loki looks down

from the live oak grove into the parking lot—shines

his flashlight slowly— seeing two still small spots

of light slightly moving.Loki and Verdandi go inside. Next morning Verdandi and

Loki awaken— walk down to their labyrinth. Vanessa and

Clive show them their son. Did the family want to leave

after this harrowing encounter so near to birth?No, word on this. Only that the boy is named Julian—

Jove’s child— There were no lion visitations for months.

Then strange sounds around dusk— chirping—

no ordinary birds could have uttered.A sudden scream at Vanessa’s house— her cat—

Marco Polo— being taken away. Vanessa and Quentin

ran outside yelling, entreating the lions not to return.

In very loud voices, they circled around their deckWhere Marco Polo had been killed. We begged them to

come inside. They were transported into near madness

by their anger. Vanessa made an altar for Marco Polo.

She didn’t see how Mother Lion could let this happenWhen she had dedicated the land by naming her child

Julian, child of Jove. In two nights, the chirping contest

resumed— lions, juvenile males with few instructions

on how to behave around humans, were at it again.Verdandi and Loki’s cat, Fez, who had been brought

in the afternoon had escaped. Near dusk, Fez joined the Puma

clan. We haven’t seen lions for more than a year — nor a deer.Julian is eighteen months and will not stay inside.

He does not speak, but roars if his parents do not

take him outdoors. This is not an ordinary toddler’s

obsession. It is extreme.His parents supervise as he runs up, down the garden

path, through the woods— seeking large birds like

wild turkeys and red-tailed hawks. -

Second Night

Verdandi awakens with a lump in her throat—

only released by tears. While she wails,

her sister, Skuld, calls in Spirit

to hear Verdandi’s dream—Carrying news of the imminent, asking Verdandi

to visit California once more. The endless enquiry

unfolds.Will Aurora return at midnight as Skuld portends?

Is Julian, a peace warrior with fresh breath,

harbinger of a new breed?Could Aurora’s glorious colors project the glowing,

pulsing arch luring an aspect of humanity

to a just end.Is Aurora lit by the disturbed solar wind? Can mother

mountain lion hear us in our sacred vessel? Will she be in

concert with songs of praise for Mother Earth?Shall we forever fear Her splendor? At two a.m.

Verdandi convened with her sisters, Urd and Skuld, in the cabin

inside the ship’s hull, asking for help from SpiritTo understand the dilemma the dream had put them in.

They closed their eyes in trust that total beauty, perfect

safety would encompass them. They disappeared—

no other humans could hang around.The path was a stairway— with seven steps for future

generations. Walking up, Verdandi opened a violet door.

Inside was an atrium with a stream running through

lush green vegetation with violets.A tiny rabbit laps at the water, takes a run for it once

he sees her. Verdandi hopes to see Mother Lion, but

hears a small frog whose croak then quells,

waits for a bird to land on her shoulder.No deal. She senses a rustling at her left shoulder.

Mother Lion caresses her hair, ears, forehead.

Verdandi turns her head, makes spiraling motions

the lion loves.Verdandi tells lion she believes in her, that she is the

matriarch of the land they both adore. She asks how to

make up for the messes she has made.Lion sits on her haunches— conveys no more humans

can be born on or live on the land. “The ones who live

here can stay, but no guarantees— no safety on hand.

Know summer is coming dryness and heat will abound.We and others need water. Make an altar. Set out water.

Keep cats away from birds anyway you can. Eat

vegetables grown in your garden. Avoid meat.

Take care of the trees. They help us breathe.You may need to leave— so may we. Do so when you are called.

Verdandi listened, then asked, “What offering can

I make?” Mother Lion replied, “Be sure to place my image

on the altar in the labyrinth.”Verdandi made a pledge. Verdandi caressed the lion

with words of deep thanks and praise. She watched

her leave the other side of the atrium into thin air and

disappear.Verdandi retraced the violet portal, walks down seven

steps, and finds herself safe within the tall ship upon the

sea. In days past, the Samí people did not see heroes and

bravery in Aurora Borealis.Instead, the spectacles were feared and respected. They

were bad omens thought to be souls of the dead. The

Samí did not speak of the lights, nor were they allowed to

tease them. Waving, whistling or singing under the lightsAlerted the Sami to their presence. Lights could reach

down, carry Samís skyward or slice off their heads. Now,

some Samís stay indoors during the lights. When Urd told

this to Verdandi and Skuld, they cried.Will all balance be lost in beauty of the sight of

curvaceous Trondheim’s shores?Will we fall down in Bodø to die in silent sighs? Is it that

close now but not time to end?Our eyes were blurred and sticky when Aurora’s gentle

crackling could be heard by ears buried by wooly caps.Could we be in collision with the ice? No, we heard the

distant hiss arise.Should we laugh at the sound of star dust igniting a fiery

tinder of atmosphere? Perhaps it was an imitation of fire

burning Mother’s forests on Ersfjord’s holy ground? -

Third Night

When Verdandi found herself no longer on the sea,

she rested her back, neck, head against the world tree—

Yggdrasil. Closing her eyes, she saw Aurora— purple,

pink, green in her mind’s eye— meditation colors.She saw how they also belonged to the world tree. She

leaned again to rest upon the rough and scratchy bark.

Her eyes closed once more and the pink turned into

fuchsia to deep violet. She was interrupted.“What can we do to benefit the future?” Skuld and

Verdandi asked Yggdrasil. “How may we possibly thank

Yggdrasil for oxygen, for music, for dance

in the swaying arms of Borealis?”Verdandi held the palette of Aurora in her third eye. She

knew it came from the sun. She knew that all Mother

Earth’s beings were star dust, brought here by forces

stronger than any poet could imagine.While Aurora rested like that, Verdandi dreamt of

Yggdrasil, of the Well of Urd, of destiny. She asked

Yggdrasil, “What does it even mean to save Earth

Mother?”Yggdrasil replied, “It means to know we are all connected.

We can see the sky veils and Aurora’s colors. We will all

go home.” Urd tells of a time the Arctic foxes made the

Aurora. They ran through the sky with lightning speed.Their tails, — large and furry, brushed against alpine

mountains — creating sparks that lit up the vast polar

sky. When their tails swept snowflakes up to heaven,

they caught the moonlight.Aurora Borealis was only visible in the winter time.

Verdandi knew little of the three grandmothers, but a

generation had skipped between the three and herself.

That was her father— Charlie Dowling. Mary Ann Ericson

Inch was her mother. Yet, he was also a son of Norway—Lover of sky, sun, desert, flight, birds, jazz, classical

music. His sister, Verdandi’s aunt, Mary Evelyn Dowling,

was nine years older than her brother, took care of her

mother after her father died of cirrhosis.She sewed for her great-nieces, ran a boarding school

in Oakland, taught nursery school for forty years,

died of ovarian cancer, refusing to eat or drink for ten

days in order to hasten her end.Verdandi dreamt of her twice — once of her aunt

bequeathing her a piece of art, the other of her laughing

at the joke that she considered death to be.Verdandi’s friction with Charlie might have been she

reminded him of his Irish father, also known as Charlie.

He died two years before 9-11. As a boy during the

Great Depression, he heard his mother, Mary Ann,Telling his father of her words, “How could you bring a

child into this world?” Mary Ann Inch, daughter of Annie

Ericson, had eight brothers, didn’t attend college, kept

house, cooked lemon meringue pie,Sewed exquisite lace blouses, pleated woolen skirts,

bound books for St. Paul’s Cathedral, felt bitter she lost

her share of the family farm, lived thirty years with her

daughter and family—Loved walking on the land. During the Great Depression,

forced to be the sole provider for her family.

Due to her husband’s alcoholism, she worked as a practical nurse.Annie Ericson of beautiful eyes and black hair gave birth

to nine children who lived to adulthood. She was born in

Ornstein, Norway. Ingeborg to Verdandi was almost a

blank slate—save for giving birth to Anne.Urd remembered an era when Aurora Borealis helped

to ease the pain of childbirth, but pregnant women were

not to look directly at them, or their children

would be born cross-eyed.Before that, lights were spirits of children who died in

childbirth, dancing across the sky. After the remembrance,

Verdandi, her sisters Urd and Skuld witnessed Aurora —

more majestic than before, and the sisters wonderedAre you more powerful than the madness of humans

bound on destruction of all life? How will life continue

on Mother Earth. Will there be help from Father Sky?Are you Spirit, Aurora? Can we believe in you? Who are

you to Aurora Borealis? Will your northern wind see us

through? Why don’t you answer our questions?Your prophecy is carried in beauty and truth over time.

Verdandi’s youngest daughter has declared she will leave

no human descendant in this world. She who is the finestCareful foster mother to abandoned cats and dogs. She

bows to her. The sisters of fate looked up to witness

the souls of old maids dancing in Aurora Borealis

waving at all those below.The next morning we find ourselves standing together

on our ship’s snow-laden deck, our best assumptions

drowned in icy tears, transforming death into

a white cocoon.It has produced a sacred butterfly spreading across

Verdandi’s neck, its wings emerging folded tightly back.

The butterfly’s brief light allows waves emotion brings.

One lump can be seen upon her throat.The enigmatic ones are deep within, set upon the wings

of a butterfly, creature of the wind. They are born of

mystery, their short lives about to end.